Excerpted from Yuval Noah Harari’s book: “Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind”, wherein he deconstructs the prevailing narrative of the Agricultural Revolution as history’s biggest fraud:

"Scholars once proclaimed that the agricultural revolution was a great leap forward for humanity. They told a tale of progress fuelled by human brain power. Evolution gradually produced ever more intelligent people. Eventually, people were so smart that they were able to decipher nature’s secrets, enabling them to tame sheep and cultivate wheat. As soon as this happened, they cheerfully abandoned the grueling, dangerous, and often spartan life of hunter-gatherers, settling down to enjoy the pleasant, satiated life of farmers.

"That tale is a fantasy. There is no evidence that people became more intelligent with time. Foragers knew the secrets of nature long before the Agricultural Revolution, since their survival depended on an intimate knowledge of the animals they hunted and the plants they gathered. Rather than heralding a new era of easy living, the Agricultural Revolution left farmers with lives generally more difficult and less satisfying than those of foragers. Hunter-gatherers spent their time in more stimulating and varied ways, and were less in danger of starvation and disease. The Agricultural Revolution certainly enlarged the sum total of food at the disposal of humankind, but the extra food did not translate into a better diet or more leisure. Rather, it translated into population explosions and pampered elites. The average farmer worked harder than the average forager, and got a worse diet in return. The Agricultural Revolution was history’s biggest fraud.

"Who was responsible? Neither kings, nor priests, nor merchants. The culprits were a handful of plant species, including wheat, rice and potatoes. These plants domesticated Homo sapiens, rather than vice versa.

"Think for a moment about the Agricultural Revolution from the viewpoint of wheat. Ten thousand years ago wheat was just a wild grass, one of many, confined to a small range in the Middle East. Suddenly, within just a few short millennia, it was growing all over the world. According to the basic evolutionary criteria of survival and reproduction, wheat has become one of the most successful plants in the history of the earth. In areas such as the Great Plains of North America, where not a single wheat stalk grew 10,000 years ago, you can today walk for hundreds upon hundreds of kilometers without encountering any other plant. Worldwide, wheat covers about 2.25 million square kilometers of the globe’s surface, almost ten times the size of Britain. How did this grass turn from insignificant to ubiquitous?

"Wheat did it by manipulating Homo sapiens to its advantage. This ape had been living a fairly comfortable life hunting and gathering until about 10,000 years ago, but then began to invest more and more effort in cultivating wheat. Within a couple of millennia, humans in many parts of the world were doing little from dawn to dusk other than taking care of wheat plants. It wasn’t easy. Wheat demanded a lot of them. Wheat didn’t like rocks and pebbles, so Sapiens broke their backs clearing fields. Wheat didn’t like sharing its space, water, and nutrients with other plants, so men and women labored long days weeding under the scorching sun. Wheat got sick, so Sapiens had to keep a watch out for worms and blight. Wheat was defenseless against other organisms that liked to eat it, from rabbits to locust swarms, so the farmers had to guard and protect it. Wheat was thirsty, so humans lugged water from springs and streams to water it. Its hunger even impelled Sapiens to collect animal feces to nourish the ground in which wheat grew.

"The body of Homo sapiens had not evolved for such tasks. It was adapted to climbing apple trees and running after gazelles, not to clearing rocks and carrying water buckets. Human spines, knees, necks, and arches paid the price. Studies of ancient skeletons indicate that the transition to agriculture brought about a plethora of ailments, such as slipped disks, arthritis, and hernias. Moreover, the new agricultural tasks demanded so much time that people were forced to settle permanently next to their wheat fields. This completely changed their way of life. We did not domesticate wheat. It domesticated us. The word “domesticate” comes from the Latin domus, which means “house.” Who’s the one living in a house? Not the wheat. It’s the Sapiens.

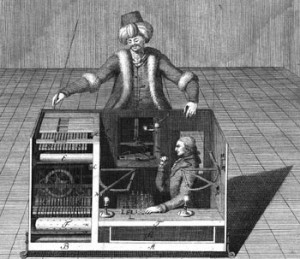

A pair of oxen and an Egyptian farmer spent their lives in hard labor in the service of wheat cultivation (Tomb of Sennedjem, circa 1200 BC).

“The horseman serves the horse,

The neat-herd serves the neat,

The merchant serves the purse,

The eater serves his meat;

‘Tis the day of the chattel,

Web to weave, and corn to grind,

Things are in the saddle,

And ride mankind.”

"How did wheat convince Homo sapiens to exchange a rather good life for a more miserable existence? What did it offer in return? ... It offered nothing for people as individuals. Yet it did bestow something on Homo sapiens as a species. Cultivating wheat provided much more food per unit of territory, and thereby enabled Homo sapiens to multiply exponentially.

“The currency of evolution is neither hunger nor pain, but rather copies of DNA helixes. Just as the economic success of a company is measured only by the number of dollars in its bank account, not by the happiness of its employees, so the evolutionary success of the species is measured by the number of copies of its DNA. If no more DNA copies remain, the species is extinct, just as a company without money is bankrupt. If a species boasts many DNA copies, it is a success, and the species flourishes. From such a perspective, 1,000 copies are always better than a hundred copies. This is the essence of the Agricultural Revolution: the ability to keep more people alive under worse conditions.

“Yet why should individuals care about this evolutionary calculus? Why would any sane person lower his or her standard of living just to multiply the number of copies of the Homo sapiens genome? Nobody agreed to this deal: the Agricultural Revolution was a trap.

References:

- Harari, Yuval Noah (2015). Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind. Harper.